Archaeologists divide time in thirds. For every third unit of time you spend in the field, budget two-thirds units of time for cataloguing and describing artifacts, conducting the research, and writing up your results. We had spent two weeks in the field, so extending this 1:3/2:3 principle, we could expect six weeks of post-fieldwork work in the lab analyzing and organizing the artifacts and samples we brought back. Naturally, we had two days in Ambon to accomplish this.

It wasn’t all bad. This was our the view from our “lab”:

We essentially set up shop at the hotel’s restaurant, laid out all our artifacts and samples, and got to work cataloguing them.

The cataloguing process involves giving every artifact or sample an accession number, essentially a unique ID that we enter into a database. We then photograph and do a basic description (a more complete description will be added to the database before the artifact/sample is analyzed) of each item.

Once we’ve finished cataloguing the artifacts they are prepped for shipment back to the US or for curation at an Indonesian facility. Some artifacts, for example, a lot of the ceramics like the ones in the picture above, were curated (stored in a museum-like setting) at Balai Arkaeologi in Ambon. Others, like the leaf samples, mangrove core samples, and artifacts we thought might date from 3500 BP, returned to the UW with the US based team for further analysis.

Packaging the artifacts for travel back to the US was quite the feat. Some items had to be “hand-carried” into the US. The mangrove and leaf-samples, for example, have to go through USDA and US customs before being stored at the University of Washington.

I’d like to remind you at this time that the mangrove samples are stored in 1 meter long PVC pipes that have been duct-taped together. We had to hand-carry these back into the US. I also had to explain in Indonesian to Indonesian TSA that these were, in fact, perfectly safe and legal to bring on the airplane.

Good news, we successfully imported all our samples and artifacts back home. Bad news, I may or may not get flagged by customs every time I travel internationally now.

After packing everything up in Ambon, our crew split up. Joss continued onto the Aru Islands to do some pilot research on his dissertation work. He has an excellent blog detailing his Indonesian adventures, called Improbable Artifacts. Definitely worth checking out. Peter traveled to Bali on a mission to find a traditional boat builder for a joint Alaska/Indonesia boat collaboration. Jenn, Emily and I returned to Jakarta for a day or so before beginning our long trek home to Seattle by way of Taiwan. In Taiwan we realized we needed to find a business center to print some last minute USDA permits, and then quickly experienced reverse culture shock as we remembered we could ask the concierge in English! Readjusting to English as the de facto language was incredibly bizarre.

Returning to Seattle and DC (in my case) mid-November from 90+ temperatures and humidity was also a little difficult.

……Epilogue…..

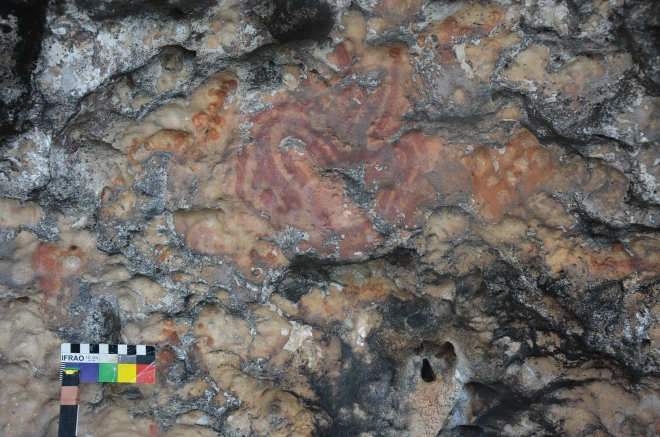

You’ve made it! This is the last post retelling the stories from our 2015 field season! We’re currently analyzing these samples:

- Mangrove cores. Our colleagues at UW were very excited to receive old dates on the 1.5 meter long core that we collected. We’re currently running additional radiocarbon dates and completing the isotope analyses.

- Joss has collected a lot of great ethnographic evidence for his dissertation work, with plans to return to Aru in the very near future if successfully funded by the National Science Foundation and possibly National Geographic.

- Jenn completed her PhD and was awarded her doctorate!!

- I have leveled up to PhD candidacy (as has Joss!!), which means we just have all the hard work ahead of us.

- Emily has analyzed her clay samples that we collected throughout Maluku and is writing up that report.

- We are working on securing funding for future field seasons. Stay tuned and wish us luck. Also, if you’d like to call your representative in Congress and ask them to increase funding to the grant-awarding agencies for the social sciences, that’d be very appreciated.

- That’s all for now folks. Terima kasih banyak untuk membaca blog-nya!